NOTES ON FINANCE, MODELS, AND INVESTMENTS

A Premier on Subordination

Extensive coverage on subordination and the capital structure.

20 min read

In this article we will dicuss - what I believe - is a quite exhaustive discussion on subordination. The only thing that might complete this discussion, and which is not much discussed, would be actually reviewing clauses in different agreements to underline the usual languae that an instrument might have when it is subordinated. However, besides that, anyone reading this completely should have a 90% proper understanding on how subordination works and why it's of paramount importance for matters involving creditors.

The structure of the article is quite straightforward. The chapter is arranged in the 5 main types of subordination and we discuss everything that might be incident in every type of subordination. In practice, lots of those subordinations are intertwined, as such, at the end, we might show how a company with various debt instruments and different types of subordination could be arranged.

PRELIMINARY

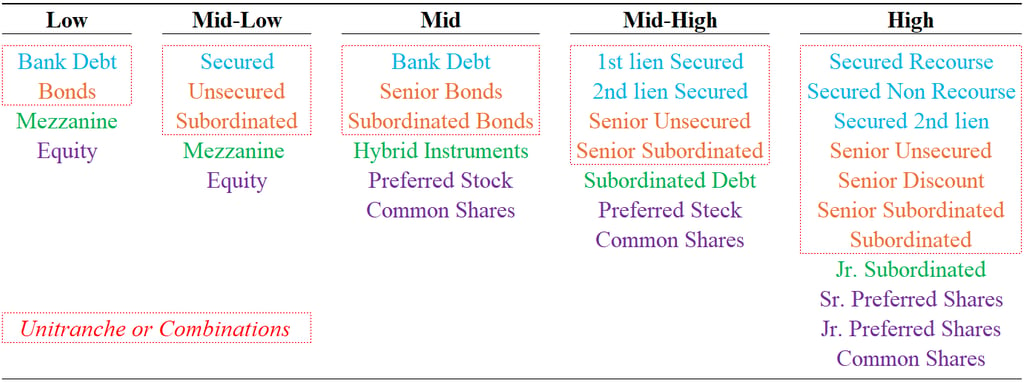

Subordination derives from the idea that every company has a capital structure. The capital structure of the company, as we discussed in previous articles, comes from teh fact taht we have different type of claims arranged in said capital structure, starting from the most basic type of claims: debt and equity. Equity is quite straightforward, however, in the debt side, we can have multiple types of creditors with different types of debt instruments arranged based on risk. Below it is shown the capital structure of a company starting from the most safe (and hence cheapest instruments. Now, lots of diffferent sources might show different variants on what actually is the capital structure of the company. Every one will attempt to establish the capital structure based in terms of priority, those at the top need to recover their debt before anything else can flow to the next creditors in teh list (which resembles a waterfall, and hence, in restructuring practice, the modeling of such distribution is performed through a "Waterfall Model"). Below, I do show from lowest to highest accuracy how a capital structure might be presented and tried - albeit it's not perfect - to categorize based on colors the category of the instrument. Also, soem capital structures might mix the name of the instrument with their positioning in the capital structure. For instance, "mezzanine finance" is as if one might say "bonds", however, in some presentations it is mixed with actual terms for a debt instrument positioning in the capital structure (e.g., senior or subordinated). Other times, there are also mixes between secured and unsecured and other instruments. This, however, just tells you that an instrument has a collateral and just sets a priority of payments on that collateral, as such, it's a mixture. We'll get into more details below. Throughout the discussion, referring back to this table will be extremely helpful.

SOME BASIC TERMINOLOGY

Now, let's set some basic terminology that we'll use along the discussion, including the different types of subordination. First and foremost many sources also use priority, ranking, subordination, preference, and other terms interchangeably. So let's see what each one of those temas.

Priority: Refers to the order of payment or entitlement to assets. It determiens who gets paid first when value is distributed (e.g., in bankruptcy waterfalls, as referred above) -- broad and general term.

Seniority: Is the position of a claim within the capital structure or over a specific asset (for instance, priority might put all the creditors together and ask "Who gets paid first? And then?", meanwhile seniority will be the "arrangement" based on priority in the capital structure. Besides, seniority is often limited to a specific entity level, meaning that it discusses just the current capital structure we have in face, meanwhile priority might put all the creditros together across an entire conglomerate and see how the flow of proceeds might go (this then, in juxtaposition, means that a junior is below a senior, hence also the differences in senior vs. junior).

Ranking: Ranking is the relative comparison between obligations against one another. It answers: "Two questions set side by side, which one stands above the other".

Subordination: Is a legal term, and it sets the legal or contractual mechanisms that establishes that one claim will "sit" below another, creating the priority, seniority, or ranking relationships which we see above. Stated differently, is the relative priority among various tranches of debt.

Hierarchy: Hierarchy means putting all the instruments together based on one or more of the criterias above and see where each one stands.

The differences, at the end of the day, are in practical sense trying to accomplish the same: Establishing which one gets paid first and which one isn't. However, it's still relevant to understand those semantics to not get confuse when one is used instead of the other. At the end of the day, all are trying to address the order of payment, so we could state the same idea through all the terms, for instance:

"Instrument A has priority over instrument B"

"Instrument A is senior to instrument B"

"Instrument A ranks higher than instrument B"

"Instrument B is subordinated to instrument A"

"Instrument A (B) stands above (below) instrument B (A) in the hierarchy"

For a finance professional the terminology might not be as important, but I can perfectly believe that for lawyers put under a litigation, especially one that requires digging through doctrines, those sort of terms can be approached from a more "philosophical" and semantic analysis and led to disputes. However, we might use them interchangeably. Let's move to other terms.

Secured vs. Unsecured

The term of secured means that the debt has collateral. A collateral is an asset that the borrower states taht if it can't repay the debt, then the lender can seize the asset (or the borrowe has to sell it and pass the proceeds). Now, from our order of payments, the secured lender is first in line to collect the proceeds of the collateral, regardless of what other claims are against the company (that is, the other creditors who do not have a claim over this asset, are subordinated to this secured lender). Absent a collateral, the creditor would need to share the proceeds of this asset with the other creditors.

The collateral is granted by a security interest (the security interest is referred also as pledge, lien on, or charge on). In large companies, the creditor despite having a secured claim can't simply immediately seize the assets it has a security interest on. The company will file for bankruptcy and everything will be managed under a Judge's supervision. This is where the term of automatic stay comes from, which means that it puts a "stay" "automatically" on the creditor's claim i.e., their claims can't be advanced (I came up with this, but it's a good association to remember the term).

Now, the creditor might state that if he can't seize the asset or those aren't sold now, then the assets might lose value. As such, bankrutpcy law, when the company is under automatic stay, puts the company in the position to prove that the asset will not be impaired (i.e. it is "adequately protected) if the company wants to continue using the asset instead of selling it. If this can't be demosntrated, the company might be forced to sell the asset and distribute the proceeds to the creditor or will require the company to grant additional collateral. If, on the contrary, the secured claim is "oversecured" (i.e., the value of the collateral securing the claim is greater than the claim), the creditor might be even entiteld to accrued interest during bankruptcy instead of just recovering the face value of its debt (as we discussed in the "Discussing Distressed Debt" article), which is more rare for unsecured creditors.

Now, the reason on why a company might grant securities comes up to two reasons: (a) the creditor wouldn't advance financing if it isn't granted a security, and (b) the company is willing to limit its financial flexibility in order to lower the cost of borrowing (the lower the risk for the creditor, the lower its reward, i.e. interest, will be).

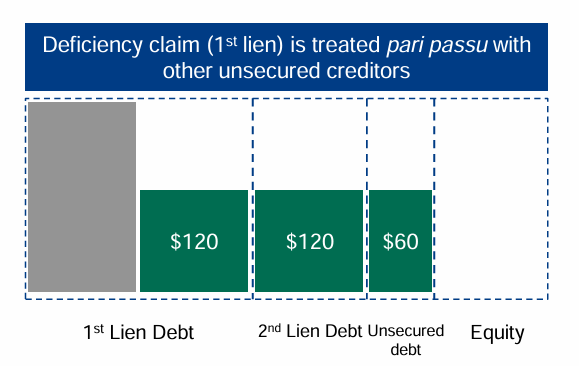

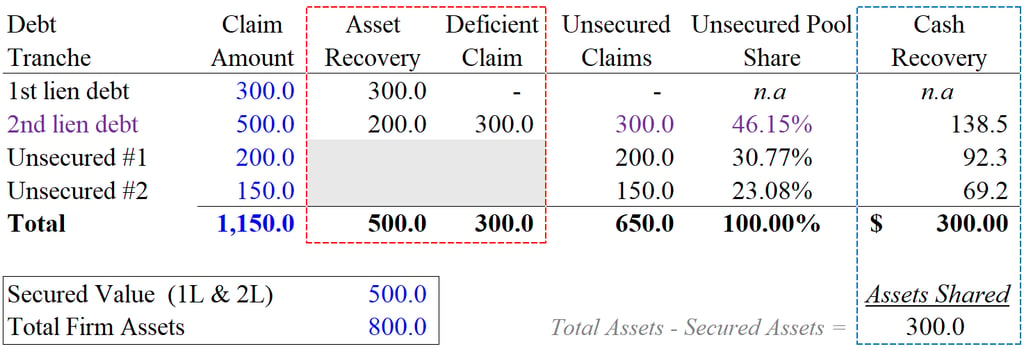

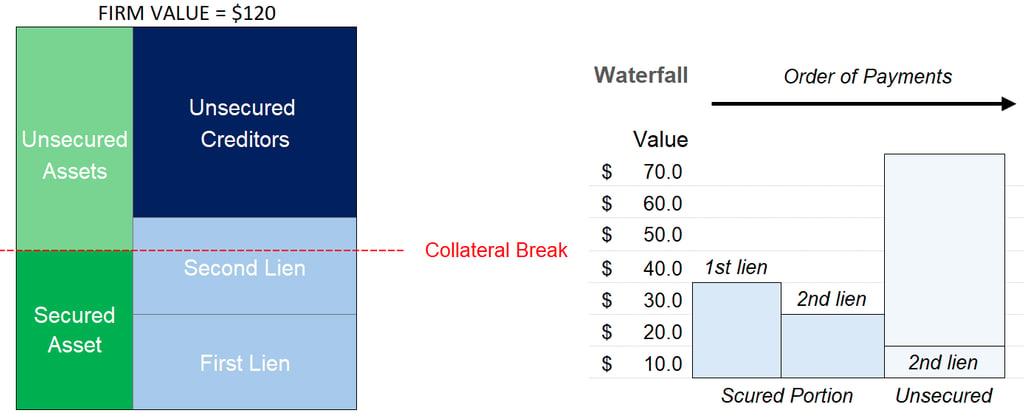

Lastly, another importance aspect in understanding in secured claims is that even if a creditor has a $500 claim and at first had $500 worth of a machinery securing this debt, in case the machinery is now worth $350, the secured creditor will get just this amount and its remaining $150 worth of debt will become a "deficient claim", meaning, it will be unsecured and it will rank pari passu (i.e. on equal ground) with other unsecured debt all else equal. For example, this is shown below:

What we're seeing in the picture is that, for instance, the creditor recovered the grey part from the asset up to the limit of the value of the secured asset, but it wasn't enough to cover the entire debt claim. As such, the remaining portion of the debt (i.e. the $120 of the 1st lien debt), becomes part of the unsecured pool and the creditor, despite being 1st lien due to the insufficiency of the asset value to cover its claim, will need to share pro-rata the remaining assets of the company up "for the taking" of all creditors (the value of all unsecured creditors, as such, is shown in green).

1st lien and 2nd lien

First lien and second lien basically sets a priority of payments over a specific asset. Both are secured, and the 1st and 2nd lien establish the priority of payments from the proceeds of that asset. For instance, if an asset is wort $500 and the 1st lien debt is worth $300 and the next one is worth $450, then the 1st lien will get paid $300 and the next one will get paid $200 from the asset ($500-$300). The remaining $250 ($450-$200) becomes a deficient claim (as in the picture above).

Now, in case someone wonders what's the use of this if the 2nd lien might still share proceeds with other unsecured creditors, the idea is that if, for instance, the creditor did not have a 2nd lien, he might had shared the proceeds with other creditors. Let's see an example on granting a 2nd lien vs. not below.

In this example, we see that the 1st lien and 2nd lien share the collateral on an asset valued at $500. The company has in total $800 worth of assets (it includes also this $500). Now, the 1st lien gets $300 on its recovery as he is first in line to get the proceeds of this asset. The 2nd lien manages only to cover $200 of its claim from the collateral. As such, he is left with a deficient claim worth $300 which is moved to the unsecured claims pool to be sharedw ith the other unsecured creditors. The percentage share is calculated by dividing the claim by the total size of unsecured claims in the pool to determine how much is allocated from teh remaining value, pro-rata on that share, to each creditor. As such, the 2nd lien manages to get only $138. Summed to his initial $200 recovered, he recovers a total of $338.5 of assets, which is a recovery of 67.7% (338.5 divided by $500) - this in the spectrum of 1st lien who recovered $300 of their claim. The allocation of 1st lien and 2nd liens is established by contract. Broadly speaking, the 1st lien and 2nd lien flow of proceeds can be someone tied to contractual subordination - the reader will for sure see resemblances below.

Now that we have introduced the important aspects, let's discuss the types of subordination.

TYPES OF SUBORDINATION.

Fives types of subordination exist: (1) Contractual subordination; (2) Lien Subordination; (3) Structural Subordination; (4) Time Subordination; and (5) Equitable Subordination.

1) Contractual Subordination

Starting with payment subordination, it is quite easy to understand. In this case, payment subordination is just the legal imperative that in an eventual bankruptcy claims will follow an absolute priority rule, meaning taht claims that are seniors to otehrs will be paid before the others.

The way in which different creditors can alter the payment subordination is through contractual subordination (referred also as "payment subordination"). Contractual subordination, as the name implies, is accomplished through an agreement between 2 creditors in which a creditor creates a self-imposed subordination by stating in the contract something along the lines of "This debt is subordinated to ABC Bond issued on the date of dd.mm.yyyy identified with so and so identification number". In this sort of subordinations, the subordinated creditor can either be an existign creditor which agrees to subordinate itself to make room for a senior creditor in teh capital structure or can be a new creditor which decides to enter in the capital structure of the company.

One mention is that legally no single creditor can ever come and declare that now he is senior to another creditor. At worst, if the first creditors did a poor job drafting the agreement, the new creditor might sit pari passu (on equal rank) with the existing creditors. To prime an existing creditor (i.e., to sit above him), you need his explicit constent which would be usually accomplished through granting such contractual subordination, as such, in simpler terms such subordination is self-imposed and often benefits 3rd parties (i.e., for instance, a senior creditor already in the capital structure might not even need to engage with the new creditor, the new creditor by its self-initative will just include in the contract that this debt is subordinated to the debt of those creditors).

The effects of a contractual subordination is that the subordinated creditors, in case they receive any proceeds, will need to pass them to the seniors until seniors are made full on their claim. Alternatively, in case a trustee manages the distribution of payments, he will be blocked (legally) to distribute anything to subordinated creditors until seniors are not repaid.

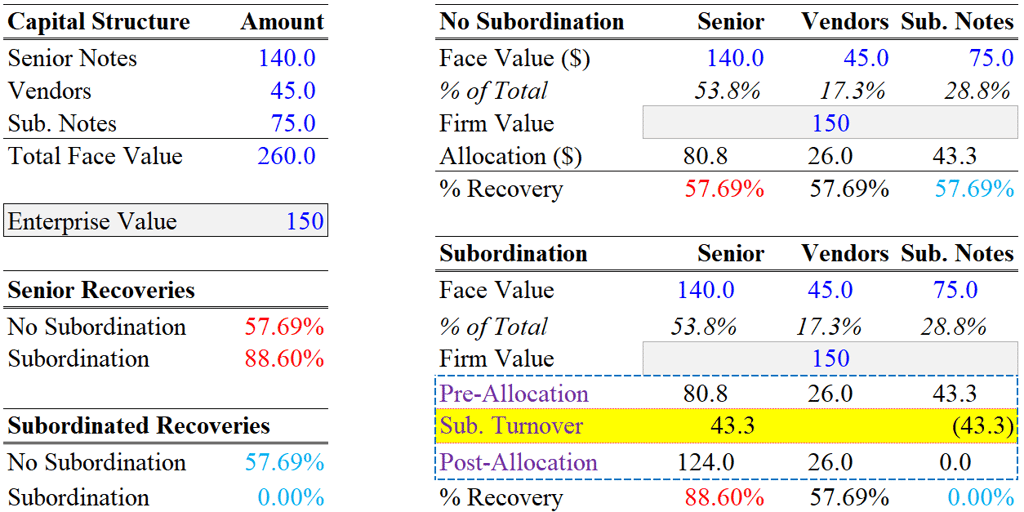

Now, let's see how this might work. Let's assume that we have the following capital structure and a scenario with no subordination and a scenario with subordination (I did leave "Sub Notes", but for the 1st scenario assume it's pari passu with the senior notes)

Let's unpack what is going on here. The Enterprise Value are the total assets of the firm that we'll distribute (or the portions of the firm that we'll distribute). The Capital Structure is just the current debt level which already reflects the subordination.

Let's move to the "No Subordination" scenario (again, assume that all are pari passu despite having vendors and subordinated notes). As you can see, in that scenario, the firm value of $150 is distributed pro-rata based on the share (%) of the claim relative to the total size of the debt pool (i.e. $260). The recovery, in that case, it's even for everyone. Everyone gets the same recovery percentage because in simple terms that would be as if taking the entire $150 firm value and dividing it by $260 (you can run the arithmetic on that, it will be clearer).

Now, let's see the Subordinatio scenario. In the subordiantion scenario the "Sub. Notes" are actually subordinated. Vendors are paid pari passu with seniors (although in practice they are often unsecured, but for the sake of simplicity). The pre-allocation, in the blue emphasized section is what they would have gotten in recoveries in case there wasn't a contractual subordination. However, once we consider the contractual subordination, the subordinated notes will pass to the senior notes all the proceeds capped up until the senior notes recovery 100% (a formula might be =min(140-80.8, [sub. notes pre-allocation), which just says that the lowest of that value between the difference to reach 100% (in case the sub. notes recovered more), or everything the sub. notes have in case it's lower than that difference). As such, we can see then in the left lower part of the image that the senior recover almost 30% more in the contractual subordination case, meanwhile subordinated creditors get 0% recovery (in cotnrast to the non-contractual subordination scenario where they also got a 57.69% recovery).

2) Lien Subordination

The lien subordination is basically what we discussed above in the "Secured vs. Unsecured" and "1st lien vs. 2nd lien" discussion. I believe that those were important terms to be familiar before the discussion, and through presenting them I believe I also already somehow touched the idea on how subordination works there. In simple terms, to refresh, the ideda is that 1st lien gets paid before 2nd lien. Those 2 creditors (the 1st lien and 2nd lien) are secured, hence, only after they are paid with the value of that asset, the unsecured creditholders will share what is left from the value of that asset altogether with the remaining asset pool of the company. I do show a illustrative waterfall to consolidate the idea:

On the left we can see the firm as the "box". The red line is the total value of the secured asset, meaning that the 2nd lien creditors are left with 1/3 of their claim deficient. On the right, then, we can see that the 2nd lien is paid up to the limit of that secured asset, after the 1st lien is paid, and the deficient claim is moved into the unsecured pool (I mentioned below in the box 2nd lien, but its portion will be paid based on the pro-rata share in the total unsecured pool, as we have seen above when discussing in more detail secured vs. unsecured).

One last mention is that if both debt tranches rank pari passu and it's a matter of 1st lien and 2nd lien, the 2nd lien, once the collateral is exhausted, can't be subordinated to the 1st lien until the 1st lien is made in full. Past the collateral value, they both rank pari passu in their respective debt tranche level. Think it this way, we have creditor A (1st lien) with a claim of $100 and creditor B (2nd lien) with a claim of $200. The collateral value is $50, hence creditor A recovers $50 and is left with $50 deficient claim (i.e., unsecured). Now, the subordination of liens works only in relation to the collateral, but they both will receive equal distributions pro-rata. However, now our unsecured claim is worth $250 (50 + 250), creditor A will receive a distribution of 20% (50/250), and the creditor B will receive a distribution of 80% (200/250), hence the $150 will be shared by giving creditor A $30 and to creditor B $120. Hence, the idea is that beyond the collateral value both rank pari passu and there is no subordination in that matter even if the 1st lien didn't recover all his debt through the collateral value as he was expecting when his debt was collateralized. This also shows that lien suboridnation is preferred to contractual or structural subordination (the latter discussed below).

3) Structural Subordination

Structural subordination can get quite complex in real cases as companies usually have dozens of entities that are interconnected between them and with creditors sitting at different levels of the entity. As such, it can get quite complex to figure out where every creditor sit. As such, we'll keep this example simple to convey the basics of the subordination.

First off, let's put in place a terminology that is important in this discussion:

Obligor: The obligor is the entity that has a direct payment obligation to its creditors under the terms of its debt instruments or other contractual commitments, this, then, some fellow legal connoisseurs might recognize the following differentiation on obligors, the obligors then can be:

Jointly Responsible - The lender can address to any obligor for the full repayment and then the obligors among them will arrange their accounts.

Sole and Only - Each obligor is responsible only for its share on the total obligation.

Primary & Secondary Obligor: Only in case the primary obligor can't repay the debt (either partially or in full), then the lender will address to the second obligor to pay the remaining of the debt.

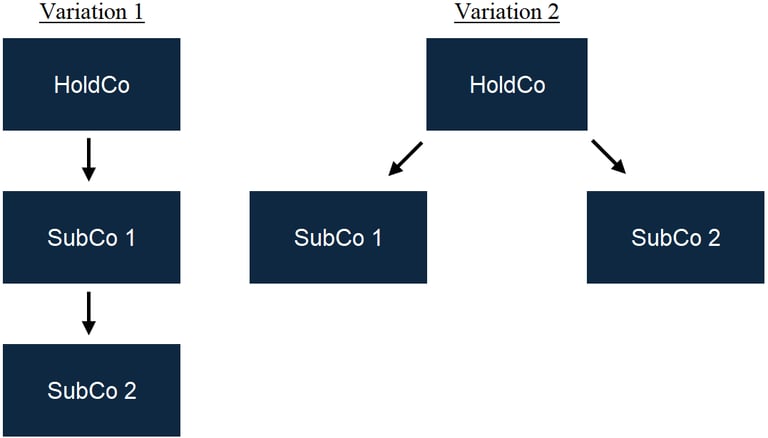

Now that introduced those terms, we can discuss how companies might be structured. Companies usually have different operations across different regions, as such, a company operating across 2 different countries might have Subsidiary 1 and Subsidiary 2. Now, this looks simpler, but what if a company had 40 subsidiaries across the world? That raises complexity. As such, the company might decide to hold all the subsidiaries under a single entity's structure so it's easier to identify the entire corporate structure. For instance, in a document instead of having to refer to all the subsidiaries, the company might say "Nike, Inc.", and when someone will check the documents, will see that actually Nike, Inc. is incorporated in Delaware, and Nike Inc. also claims to be owner of 40 subsidiaries. This company that holds all those subsidiaries is referred in discussions as "HoldCo". The subsidiaries are referred as "SubCo". Put it differently, HoldCo is like the parent, and SubCo(s) are like his children. Each line symbolizies ownership. In the Variation 1, HoldCo owns SubCo 1, and SubCo 1 owns SubCo 2, so we can say taht HoldCo holds indirectly SubCo 2. In Variation 2, we see now that HoldCo holds directly both SubCo. This has implication on our discussion, so keep it in mind.

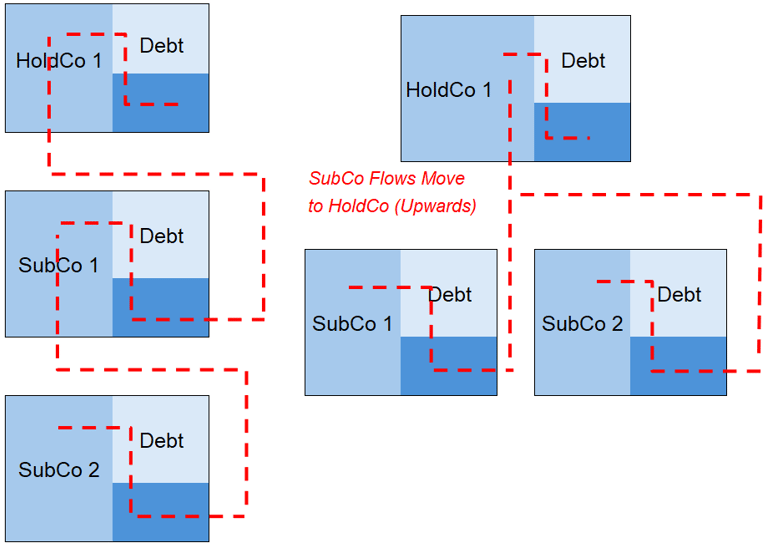

Now, in practice usually HoldCo are "empty" shells. As we stated, they are used mostly to keep together and in a single nice place in documents all the SubCo. SubCo are the companies actually engaged in business activities (they are usually referred as "OpCo" in discussions). The flow of funds follows this sort of structure in terms of distribution. As we stated, because they are linked through ownership, it means that the company owning the other company sits as equityholder. For instance, HoldCo owns SubCo as an equityholder, not debtholder. This means that in an eventual liquidation of SubCo 1, creditors are paid before, and what is left is passed to HoldCo 1 to be shared among its capital structure. The below red lines show the flow of proceeds (emphasis that they go from the lowest levels upwards in this order).

Now, what one can observe from those flows is that, for instance, if SubCo 2 in the left has $100 worth of debt and $50 in cash or assets to distribute, then equityholders will get $0. This means that there is no more cash to be sent upwards across the corporate structure and there is nothing that can be done. This then, underlines our 3rd sort of subordination: Structural Subordination.

For instance, imagine that SubCo 2 in the left has some bonds, and that SubCo 1 above them has senior loans. Based on terminology one could say that the bonds, as they sit lower in the capital structure, are subordinated to senior loans. However, when we consider the flow of cash, the senior loans are subordinated to the bonds at the corporate level (i.e., when we consider the entire corproate structure of the borrower, because, for instance, they could indeed by senior to all the other debt instruments that sit at the capital structure of SubCo).

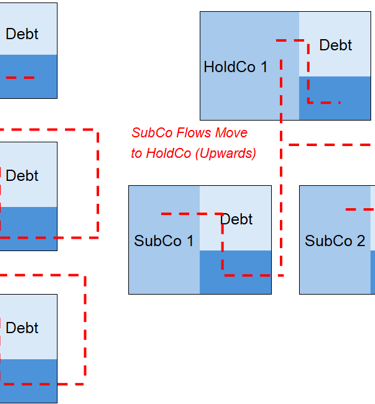

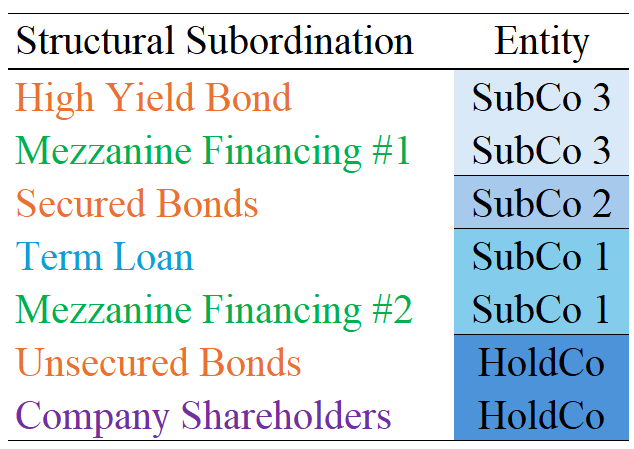

On the right side, if we have the bonds at SubCo 2 and the senior loans at SubCo 1then they are not subordinated and they are isolated in terms of repayment. Each entity will repay its debtholders as much as it can and if there is something left it will be passed upwards to HoldCo. If, for instance, the senior loans at SubCo 1 are not made full but there is still value left in SubCo 2, without complicating it, the SubCo 2 and the HoldCo have no obligation to pay in rest with what remains (they could, but it would be a philantrophic act more than some sort of logical transaction). This then sets the idea that structural subordination reigns over the usual subordination that one might expect in a capital structure (as we introduced on how different instruments sit across the capital structure), the structural subordination might put in terms of priority, when looked at the entire company, to something like this:

I do show in colors how, if they were at the same entity the usual structure would be blue > orang > green > purple. However, when we consider the flow from a structural subordination standpoint, as they are different entity levels, the proceeds will flow in this order. As such, the HoldCo level debtholders have the biggest risk as they are paid only after everyone else is paid (and, by the way, the company shareholders, especially in public companies, are where the shares sit). One thing as a side mention is that at HoldCo level usually debt might have PIK toggles in case creditors at subordinated companies block payments towards HoldCo (e.g., through distributing dividends to repay the debt at HoldCo level), so creditors at HoldCo can accrue payment on their debt.

Now, this can get more complicated if we incorporate: upstream guarantees, downstream guarantees, and sister guarantees, and the substantive consolidation which is a doctrine more prevalent in the U.S. But we'll discuss them another time, as this is already getting long. Let's move to the next type of subordination.

4) Time Subordination

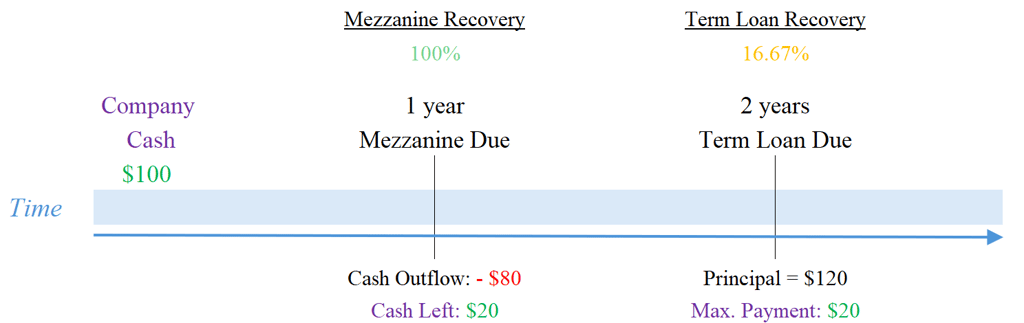

Time subordination is a coin termed by the industry. Legally, there is no such thing as a time subordination, so - this is where our terminology comes at hand - what it really means is time priority. Put in simpler words, time priority means when the debt matures and needs to be paid. This is very simple to understand, so let's give an example. Let's say that we have $100 in liquidity and we have mezzanine debt coming due in 1 year worth $80, after 2 years, comes due the term loan worth $120. The term loan is senior in the capital structure, but because the mezzanine has to be paid earlier this creates a sort of "time subordination" which puts the term loan at a higher risk. This can be seen below in a simple chart. The idea is not hard, but helsp to consolidate it.

Now, to not stop here, let's add some more discussion on this. Term loan creditors aren't actually stupid and they know about time subordination, so what they'll do would be to incorporate a negative pledge in their credit agreements stating that the company can't inccur any debt that comes due before their term loan (for the record term loans are usually for 3-5 years). This provision prevents other creditors "priming" from a time (i.e., repayment) perspective the term loans. In case the company adds more debt, because they breached this covenant, the debt of the term loan will be "accelerated" i.e., will need to be repaid immediately. Now, put yourself in the shoes of the mezzanine investor in our case. Let's say you want to advance $80 to the company. The company currentl has $100 in cash. If you know that granting this mezz loan to the company would trigger an acceleration on the term loan then it would deter you because the company would need to repay $120 to the term loan and will be left with $60 ($100 + $80 = $180 - $120 = $60). So, the company is put in a worse position altogether because they don't have much cash (so probably liquidity for daily operations is also impacted), and let's say that 1 year comes due and the company was able to generat only $10 in this period because of that acceleration clause with constrained their liquidity. As a mezzanine creditor you'd recover only 87.5% of your debt (you not only didn't make any profit through interest, but you also didn't even break-even from a credit nominal standpoint). This shows how acceleration clauses can deter new creditors from lending. However, sometimes this might be done intentional to "kick" existing creditors from teh capital structure in case that management and the new creditors find in this some sort of value (e.g., imagine that the company wants to pursue some riskier projects and needs more flexibility and it brings new creditors that have the stomach for such risky investments, then, they will just quick the more risk averse creditors, i.e. the bank creditors, and they will carry forward their own capital structure to be adjusted to the sort of operations the company will engage in). Let's move to the last type of subordination, which is a bit special

5) Equity Subordination

Equity subordination is a legal mechanism in which certain loans advanced by shareholders or other creditors to the company are subordinated in the last place in the capital structure and considered as equity i.e., will share whatever proceeds are left with the rest of equityholders. Stated differently, subordination is a doctrine that allows the court to lower the priority of a claim. To apply the doctrine, 3 things must be met cumulatively:

The claim must have engaged in inequitable conduct

Its misconduct must have injured other creditors or conferred an unfair advantage

It shouldn't conlict with other provisions from the bankruptcy code.

Generally, equitable subordination is applied when a creditor exercises lots of de facto control over the company in such a way that it advantages him (hence the misconduct). The implications of equitable subordination is that - reviewing our capital structure - the creditor would be put in the "purple" category (i.e., equity claim), hence he'll be paid the last.

***

As such, this concludes what I believe is quite an exhaustive overview of subordination (albeit might follow with a new article to discuss more in depth some aspects, specifically in the structural subordination). So let's review actually across all those types of subordination some principles that are foundational no matter in what situation you find yourself analyzing a subordination, those are:

A creditor can't get subordinated without his explicit constent

Unless stated the contrary, all debt instruments rank pari passu (i.e., they are equal)

Constent or law is the only source of subordination and hence can be enforced legally.

The closer the creditor to the assets, the higher his priority all else equal

Distributions are made based on the absolute priority rule.

This concludes our article on "A Premier on Subordination".

The content on this blog, including any related materials such as newsletters, is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as financial, legal, or professional advice. Readers should consult with their own advisors before making any decisions based on this information. The author(s) disclaims all responsibility for any actions taken or decisions made based on the content of this blog. The aim is to promote general understanding and knowledge.

Contact

dealsandmandates[at]gmail.com

© 2025