NOTES ON FINANCE, MODELS, AND INVESTMENTS

Discussing Distressed Debt Investing

Discussing some basics on distressed debt.

12 min read

In this article we'll discuss in broader terms the field of distressed debt investing. We'll start by offering an overview on what exactly is distressed debt and then I might discuss things that I find relevant and interesting to understand.

Let's dive in.

WHAT IS DISTRESSED DEBT

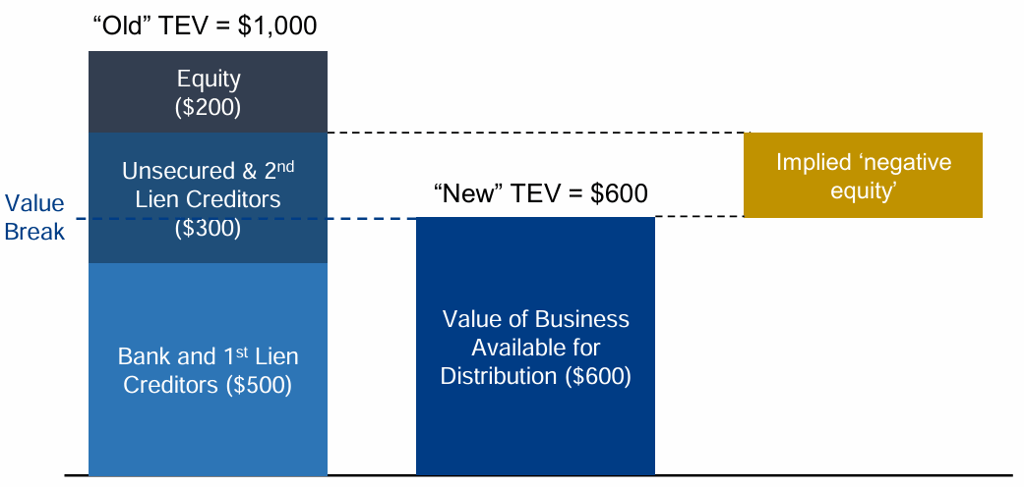

The concept of distressed debt, as the name implies, arises when a company’s debt trades at depressed prices to reflect a state of distress. As we discussed in the LBO Part I article, the composition of a company can be seen as a “box”: once equity is exhausted and falls to zero, creditors are the ones left on the hook for losses. Anticipating such outcomes, investors may pressure the company into taking action - whether restructuring efforts or filing for bankruptcy - before the firm’s value is completely eroded and creditors are left with nothing to recover.

Distressed debt emerges when the business reaches this point, where its value must be compressed into a new, lower figure reflecting the current asset base. In such a scenario, unsecured and second-lien creditors stand to lose most or all of their money, while equity is entirely wiped out. The fear of this outcome explains why debt trades at lower levels in the market, as sellers try to exit before an eventual “readjustment” of the business’ “box,” or, more precisely, its capital structure.

At its core, the concept rests on the balance sheet equation: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity. As equity is removed, creditors are effectively “trimmed” as well, so that the liabilities and equity side aligns with the assets side. For those more advanced, this rebalancing is not based on the book values on the balance sheet but rather on the present value of free cash flows and the present value of interest-bearing liabilities, with adjustments made according to the company’s debt capacity. For now, however, this serves only as an overview of why and how distressed debt situations arise.

The reasons why a company might fall into such a situation can be diverse. It could be that the business has lost customers, suffered extraordinary events such as a tsunami, or simply fallen behind due to technological change or heightened competition. The list of possible causes is endless, but they all matter to an investor because they help in assessing whether the situation is temporary and correctable, or whether it signals a deeper, structural decline that will only worsen over time until liquidation becomes inevitable.

The first case is what the industry refers to as a "going concern," meaning the company is preserved and allowed to continue operating. If that is not feasible, then liquidation is the only path. The comparison, therefore, is framed between going concern and liquidation value.

If the company is worth keeping, creditors and management sit together to decide on the path forward that allows operations to continue while minimizing losses for creditors. The simplest solution would be to wipe out all debt and give the company room to breathe, but no creditor would ever accept that, especially since not all creditors bear losses equally. Some may lose more, others less, depending on their position in the capital structure, as we will explore later.

MARKET IMPLICATIONS

Now, let us say that management sits down with certain creditors to discuss what to do with the company. At the same time, the market begins to notice that the firm is breaching covenants or showing weaker performance. The first signal often comes from the equity price, which starts to decline as shareholders, aware of the distress, no longer see much value left. Equity valuation techniques generally incorporate expectations of growth into the calculation of value. Comparables, for instance, lose their relevance if peers are expected to grow while this company is not. In such cases, shareholders exit their positions, which further depresses the stock price.

Someone reading this might say, fine, this looks like a classic distressed debt environment. But before focusing entirely on the debt, why not look at the equity? After all, it could resemble a value investing opportunity. Perhaps the market is overreacting, and the company has the potential to rebound. If we take the graph above, it may suggest that the company’s value has fallen below the total size of its liabilities. Yet what if the true value of the business is higher, such that equity should be trading at 50 percent of last year’s value instead of the current 15 percent? That possibility opens an interesting discussion, which is worth exploring further.

Equity Considerations

First off, we cannot really use the term “distressed equity.” Equity is equity, and the fact that it is trading at a level that is 90 percent lower than last month does not make it “distressed.” Prices simply fluctuate to reflect fundamentals. Should an investor buy this equity? In most cases, no. Creditors across the capital structure typically have a clearer view of what the company’s value should be, and if any debt is trading below 80, that is already a strong indication that repayment in full is in doubt. If the company ultimately heads into liquidation, equity will almost certainly be wiped out.

Now, let us say the company is put into bankruptcy to determine its true value. Valuation conflicts abound in such cases, which I will not get into here. The key point is that the bankruptcy process centers on creditors and the attempt to repay them in full. It is not difficult to see why equity holders are wiped out once you follow a simple sequence of questions: can the company repay creditors? No. Can it repay them in full at the current claim size? Unsure. No management will openly say “no,” which makes the conflict of interest obvious. The reality is that if current debt cannot be repaid, it must be amended or restructured, otherwise creditors will force liquidation. Creditors unwilling to accept amendments will demand asset sales to recover value. Yet from the perspective of other creditors, this only weakens the operational value of the business and further reduces the chance of repayment. Bankruptcy, however, changes the dynamics by limiting the influence of those creditors who are protected, such as oversecured or collateralized lenders, and shifting the process toward those most at risk of being impaired.

The company, it is worth remembering, is put into bankruptcy because it failed to repay debt that came due and the creditor refused to extend or excuse it, believing the company might be in an even worse position later, which is precisely why bankruptcy was triggered. Now, if the company could have sold its assets, why did it not do so earlier? The answer lies partly in the law, which allows certain transactions to be challenged for up to one or two years depending on the jurisdiction. If a transaction placed some creditors in a worse position while benefiting another creditor or the shareholders, then the favored party may be required to return what they received so that the estate, meaning the firm, is restored to its prior value. Bankruptcy solves this problem by bringing asset sales under the supervision of the court. Any sale must be approved by a judge, and through this process the company can dispose of assets in a way that withstands challenge, ultimately allowing it to emerge from bankruptcy after having liquidated creditors in an orderly, legally sanctioned manner.

In this case, shareholders may still retain their shares. It is not a prerequisite that equity be wiped out unless the company’s value truly falls to zero. A firm can enter bankruptcy simply for failing to make a payment, which is why it is important to distinguish between two tests: (i) the balance sheet solvency test and (ii) the cash flow test. What I have discussed so far relates to the cash flow test, where a company that misses a payment can be forced into bankruptcy, as is possible under certain European laws, such as in France. The United States, however, follows a balance sheet test, under which a company is placed into bankruptcy once its value is lower than the contractual face value of its liabilities. This distinction matters, because when the balance sheet test applies, the dynamics of bankruptcy shift considerably.

In the U.S. model, a company is placed into bankruptcy only when its asset value is believed to be lower than the value of its liabilities. This explains why much of the U.S.-focused literature emphasizes that equity is “wiped out.” Under a cash flow test, however, equity may still retain value. It is also worth noting that bankruptcy is not triggered solely by financial distress. A company may enter bankruptcy to consolidate claims into a single process, or to gain leverage in renegotiating burdensome agreements, such as union contracts. With that clarified, let us return to the debt side and continue along that line.

***

Now, let us return to debt. Suppose we are investors looking at a distressed company from the debt side. The bonds are trading at 64. Is that a buy or not? The answer depends entirely on how we value the company. Let us examine this more closely.

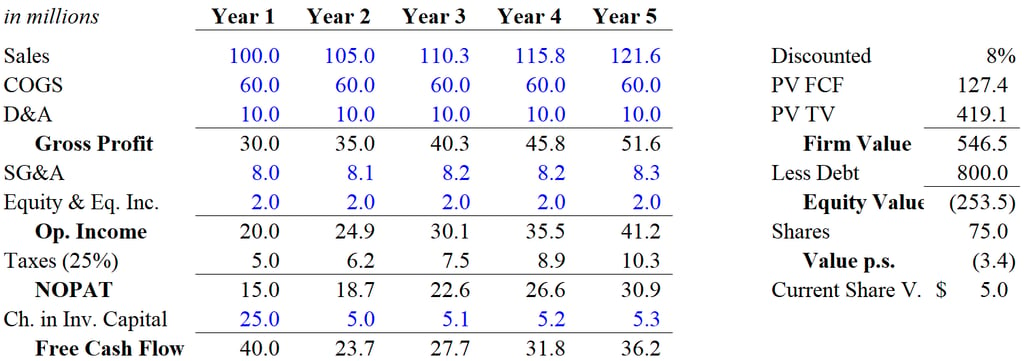

Now, based on our valuation estimates, the company’s equity value comes out at negative 253. Yet in the market we see equity trading at 375 dollars (75 shares at 5 dollars each). If the bonds are not trading at depressed levels, we need to carefully recheck our assumptions. When the market does not seem to share our view, it is a good signal to revisit the analysis. Still, let us assume we rerun the numbers and the evidence holds—earnings calls, maturity walls, and broader market signals all suggest this valuation is correct, and the company faces a looming liquidity issue. The market may still be pricing equity positively, perhaps irrationally, say due to retail speculation. Looking instead at the debt tells us a different story: the term loan (1L) trades at 97, the secured bonds (2L) at 87, and the unsecured bonds at 53.

The way to read bond prices is usually in percentage terms of purchase price, though in reality they reflect the current value of the debt relative to par, meaning the amount due at maturity. Debt prices fluctuate with interest rates, so we should not expect healthy companies to always trade at exactly 100 unless the instruments are floating rate. A range of plus or minus 10 from par is generally normal. Looking at the current prices, the term loan is not really selling at a discount. Trading at 97 likely reflects either the time value of money or an incentive for someone to take it off the lender’s hands, since the lender may prefer to avoid the hassle of a bankruptcy process. Even if fully secured and almost certain of repayment, from the creditor’s perspective cash in hand today is preferable to cash tomorrow with even a small chance (say 2 percent) of collateral challenges or procedural delays caused by junior creditors. Such disputes could prolong the case and tie up their money far longer than intended.

Now, the secured bonds (2L) are also trading at a relatively high price. The reason is straightforward: they are secured, and investors are confident that their value will largely be covered. Still, they trade slightly lower than the first lien, which reflects the possibility that the collateral may not be sufficient to cover the full value of their claim, even though they are secured on that asset. In other words, they expect part of their claim could end up deficient. For more detail on this dynamic, see our other article “A Primer on Subordination.” As a result, second lien bonds trade somewhat depressed relative to the first lien loans, but still at a stronger level compared to unsecured debt.

Lastly, the unsecured bonds are trading at 53, which suggests investors expect to recover somewhere above 50 percent of face value in an eventual bankruptcy distribution. With that in mind, let us return to the capital structure and consider how this might actually play out, and what exactly each class of creditors is pricing into their positions.

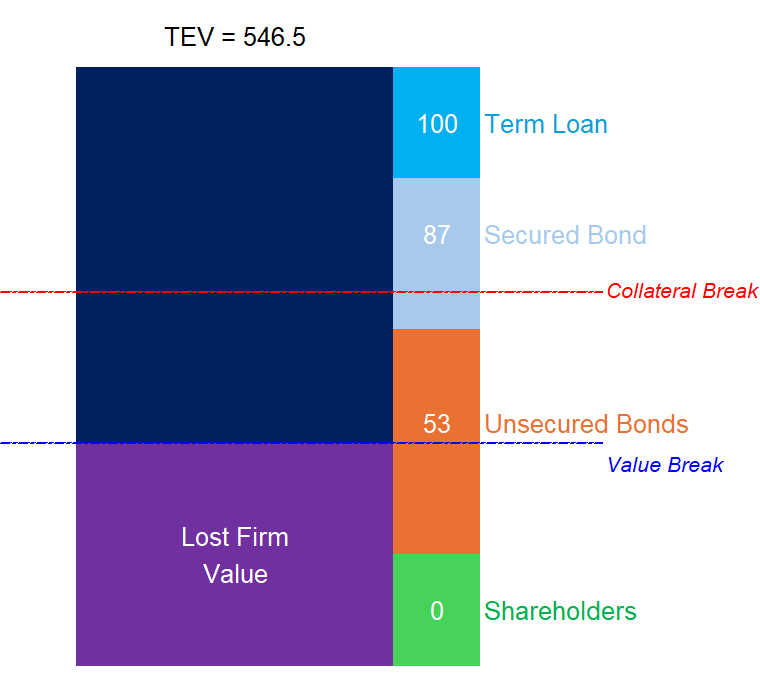

What we see here is essentially the combination of total enterprise value with the claims of each creditor class. The term loan is recovered in full, so we can assume a 100 percent recovery there. The secured bond, however, will only recover part of its claim from the collateral, with the remainder spilling into the unsecured pool to share recovery alongside the unsecured bonds, since the collateral break will not fully cover them. In this sense, both the secured and unsecured bonds are really pricing the uncertainty of that “value break” line. If the break falls between the orange and green points on the capital structure, then secured bonds would be almost certain of full recovery, aligning their pricing much closer to par. Still, bankruptcy outcomes are rarely straightforward, and recovery levels can take years to resolve. Unsecured bonds, priced at 53, are signaling expectations slightly above half recovery. At the same time, creditors may be factoring in the possibility that the value break shifts upward, with total enterprise value rising from undervalued assets or other adjustments, giving them more than what the current market suggests.

From a distressed debt investor’s perspective, this stage is all about expectations. Attention typically centers on the unsecured bonds, which represent the real “pain point” in the capital structure. This tranche, along with the secured bonds that are partially impaired, will likely form the voting classes on any plan of reorganization, since non-impaired classes do not vote. An investor might believe the company’s true value is closer to 700, which would push unsecured recoveries higher, making that tranche more attractive than the secured bonds, whose upside is capped by their smaller deficiency. To illustrate, imagine a 200 range between the collateral break (red line) and the value break (blue line). If the company is currently valued at around 550—rounded for simplicity from our earlier PV—but we believe TEV could reach 700 due to undervalued assets, a stronger market, or new buyers, then the 100 of potential recovery expands to 150. That implies a 150 percent increase in recovery prospects for the unsecured bonds and the unsecured portion of the second lien bonds.

The unsecured bonds were trading at 53, which on the optimistic side implies roughly a 53 percent recovery, with perhaps 3 percent of optimism priced in. Let us assume that, without such optimism, the fair assessment of value put recovery closer to 50 percent. In that case, investors were essentially expecting to recover half their claim. But would they truly reach 50 percent, as priced at the outset, and then simply add the 42.6 percent increase in pool size to arrive at 92.6 percent recovery? Not exactly. Let us examine this more carefully.

If the unsecured pool were made up only of the unsecured bonds, one could simply see the value break falling in the middle of their claim, implying that at 50 percent of TEV they recover 50 percent. However, once we introduce the unsecured portion of the second lien into this pool, recoveries are diluted. For example, assume there was originally a 200 unsecured claim with a 50 percent recovery, giving them 100. Now, add the 50 of unsecured deficiency from the 2L, which is also effectively pricing at 50 percent recovery. The total unsecured pool becomes 250 (200 unsecured plus 50 unsecured portion of 2L). Allocating proportionally, the 2L unsecured portion represents 20 percent (50/250) and the unsecured bonds 80 percent (200/250). Distributing the 100 recovery, 20 goes to the 2L portion and 80 to the unsecured bonds. That leaves the unsecured creditors with 80 on a 200 claim, or 40 percent recovery from par. In this case, an investor might be tempted to short the unsecured bonds trading at 57. For curiosity, we can also approximate the 2L value: the gap of 20 to 50 for its unsecured portion implies a 13-point swing in bond pricing. With 13 points equating to 30 of value, dividing 30 by 13 and multiplying by 100 yields roughly 230, with adjustments of plus or minus 15 to 20 to reflect risk factors, similar to our earlier discussion on the term loan.

We have not yet considered the “hidden” value of 150 that we believe the market has overlooked. Applying the same 20 percent allocation between the unsecured portion of the 2L and the unsecured bonds, we arrive at 50 for the 2L and 200 for the unsecured, each recovering 100. At this point, both the 2L and the unsecured bonds could look attractive as long opportunities. But it is worth stepping back and thinking about the actual return we are annualizing. For the 2L trading at 87, a move to par would mean a 14 percent gain (ignoring interest and other features). For the unsecured bonds, recovery at 107 would imply an 88.6 percent return. If we are extremely confident in our valuation, then going long the unsecured bonds makes sense. But if our assumptions are wrong, and that hidden portion turns out to be worth only 80, then the unsecured recovery would fall to 32 percent, meaning a purchase at 57 results in a 42 percent loss. By contrast, the worst case in the 2L is different: since its unsecured deficiency shares the same pool, the price of the 2L adjusts in line with that dilution, cushioning the downside relative to the unsecured.

Again, think about what this means in the worst case scenario. If the downside is a 42 percent loss and the upside is an 88.6 percent gain - which is admittedly a stretch, but let us assume these are the only two possible outcomes - then with equal probabilities of 50 percent each, the expected value of the trade is 32.5 percent. The upside is more than double the downside, giving us an asymmetric return profile with a two-to-one reward-to-risk ratio. Framed this way, it looks like a bet worth taking.

This concludes our discussion on distressed debt. I may continue this as a series, exploring further “hypothetical” scenarios to shed more light on how investors think through these situations.

The content on this blog, including any related materials such as newsletters, is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as financial, legal, or professional advice. Readers should consult with their own advisors before making any decisions based on this information. The author(s) disclaims all responsibility for any actions taken or decisions made based on the content of this blog. The aim is to promote general understanding and knowledge.

Contact

dealsandmandates[at]gmail.com

© 2025