NOTES ON FINANCE, MODELS, AND INVESTMENTS

Financing the LBO: Part II

Continuation of the first part I on financing sources for buyouts.

7 min read

In the previous part I we discussed some foundations on LBOs, mainly what are those, and the mechanics behind them (including some discussions on how Sponsors approach LBOs). In this part we present the main instruments and how those are modeled. The spliy will be discussing some foundatins widely applicable for all instruments, and then we'll see explain a bit each debt instrument that might sit in an LBO and how to model it (i.e., the calculations of it).

Let's dive in.

FOUNDATIONS FOR DEBT MODELING

At its core, all models follow a sort of precedent-based analysis where we analyze our current year or subsequent years based on the previous year results. This follows the accounting logic on how different entires in one year inevitable affect the starting entries on the same year, and, at the end of the day, a company is just the continuation of its operations of the previous year which in finance and accounting it is tracked based on analyzing financial statements assigning a book value to those changes. However, for debt modeling, our most important concern is the Cash Flow Statement which is the tangible cash taht the company has in a period and which is what lenders expect to receive. As such, the first important element in understanding debt calculations is that

Some Accounting

The 3 financial statements have lots of thinks so we'll be quite a distraction to discuss how all of the are linked. As such, we stick to those related to debt.

First and foremost debt is highly tied to cash flows. When we pay interest or debt we have a cash expense and we inccur debt we have a cash inflow. As such, our accounting flow on how the debt elements go through all the 3 statements will be primarily in getting to cash flow statements.

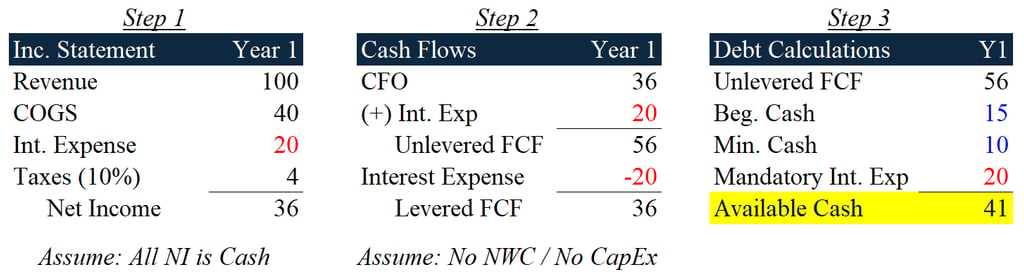

Now, let's review the entires that impact our financial statements. For simplicity, we do ignore lots of items in the 3 financial statements so we only focus on what's important. Below are the entries and our goal is to understand the yellow cell. Let's go through it.

First and foremost we start with the Income Statement. Our company has $100 in revenue, we then deduct COGS leading to $60 gross profit. We exclude here and make the exaggerated assumption that the company has no other costs, and hence, we get to the interest expense. $60 minus $20 interest expense = $40, and applying a 10% taxes to that $40 we pay $4 in taxes and we're left with a $36 which we assume to be it all cash.

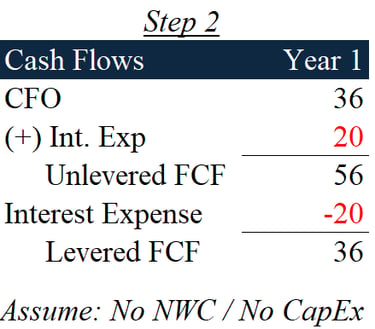

Now, in the cash flow statement we start by adding to our net income and substracting what are non-cash expenses to get to our cash flow from operations and we assume that the company has no other expenses. When we add Cash Flow from Operations and Cash Flow from Investing (which includes Capital Expenditure and Acquisitions), we get the "Unlevered Free Cash Flow" of the company, which is the cash teh company has before accounting for any financing expense (such as interest or dividends). The reason we added the $20 to the $36 is precisely to remove the impact of the financing on NI, and as such, rebuild back to get the Unlevered FCF. Now, if we want to go to the levered FCF, which accounts for some mandatory financing, then we just deduct the interest expense and we get $36. I decided to keep $56 and show on the last step this deduction.

In the last step, we take our FCF, we add the beggining cash (which we'll find in our balance sheet, which is the cash flow we had in our previous year), we'll deduct the minimum cash we need to keep on the balance sheet to continue our operations, then we also deduct the mandatory interest expense, and we're left with "Available Cash" to engage in financing aspects.

This means that this cash can be employed to distribute dividends or alternatively to repay more quickly our debt or alternatively to inccur more debt and support a maximum of $41 (interest (very risky to have an interest expense aalmost teh same as FCF). As such, this will dictate how much more debt we can add. However, this shouldn't directly mean that we should add debt. As you remind in our Part I we actually discussed how much debt should the company has, and, besides that, we also should put the debt at use so that debt delivers a return that is above the cost of the debt (that is, in finance terms, the Return on Invested Capital needs to be above the Cost of the Debt).

If all of this is confusing, reviewing some accounting notes or how the 3 statements are constructed should be enough to clarify it.

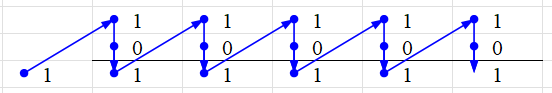

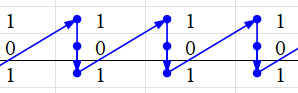

The Cork-Screw Technique

The next observation on debt is that it follows a cork-screw technique as shown bellow where the end of our balance is moved to the next year at the starting balance. The 0 just shows us the change on the initial balance that will influence the change on the closing balance that will be carried to the next year. This modeling technique is shown below

THE DEBT INSTRUMENTS

Now that we have the foundations we can start looking into the debt instruments. We'll discuss: (1) The Revolver; (2) Term Loans; (3) Bonds; (4) Mezzanine (more precisely, PIK Mezzanine); and (5) Preferred Shares.

1) The Revolver

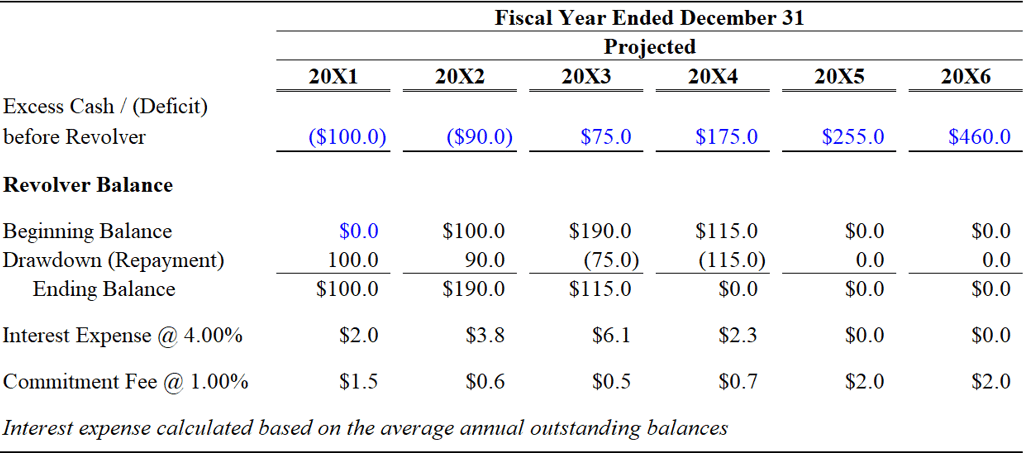

The revolver, not to be confused with a gun, is a relatively simple instrument in practice. It is a revolving credit facility that typically sits at the top of the capital structure and is priced at comparatively tight spreads. Revolvers usually carry covenants, and their economics (i.e. interest and fees) depend on the terms negotiated between lenders and borrowers. They can be structured either on the basis of assets (an asset-based loan, or ABL) or on cash flow (a cash flow revolver, or CFR). This distinction mainly affects the limits on how much the borrower can draw (albeit the mechanics remain unchanged). Those mechanics are straightforward, as shown in the example below. In practice, when the company faces negative cash flow it may borrow under the revolver to finance operations, and when cash is positive it may repay outstanding amounts (this, as well, being represented below). Carrying a balance on the revolver comes with interest on drawn amounts as well as a spread applied to undrawn commitments, commonly referred to as the commitment fee.

In this example, the average annual outstanding balance simple means =sum(beginning balance, ending balance) / 2 * interest expense. This will give us the interest expense for each year.

Term Loans

I will dedicate a separate article to term loans, as I believe there is much to cover. Although they are generally regarded as straightforward instruments, they become more interesting when examined through the lens of their secured nature. For now, however, we can focus on the most traditional form of term loan, the type most readers would be familiar with. Term loans are typically secured and rank at the top of the capital structure of the borrowing entity (below the revolver, albeit lots of times banks advance both at the same type). Terms loans are differentiated mainly based on the category of lender and based on their amortization.

Investor Base

Regarding the lender category we have TLA, TLB, TLC, and more rarely TLD. All of those terms basically mean Term Loan [Letter], and each letter denotes the sequence of lenders that sit pari passu with the TLA, which is the classic term loan advanced by banks that are secured. Subsequent loans (i.e. TLB, TLC, and TLC) might also share the 2nd lien on the TLA's collateral or might be secured by other company's assets which would then create a waterfall among them before passing any remaining assets to unsecured notes which sit below term loans in the capital structure. However, I will discuss in more detail subordiantion in another article given this raises interesting technical discussions on "who gets paid before whom".

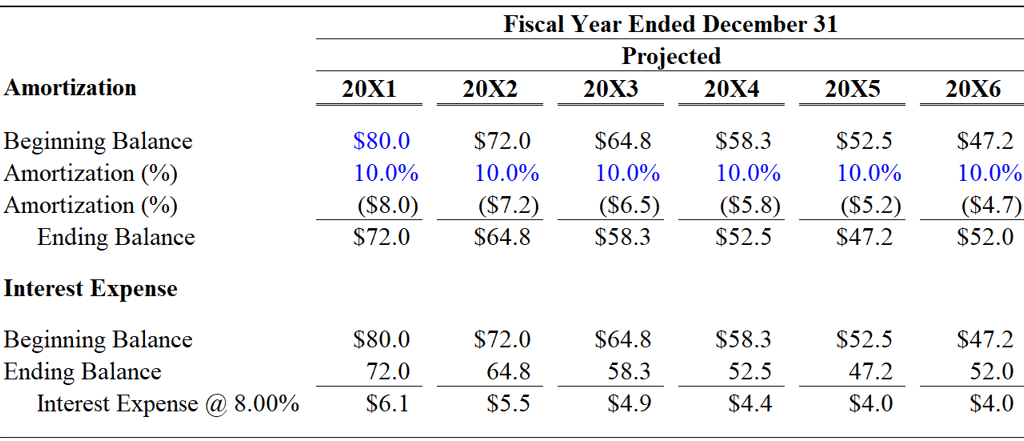

Amortization

In my view there are 4 main types of amortization (5 if we include PIK structures, but I will keep them separated): (a) equal principal amortization, where the borrower repays a fixed amount of principal each period plus interest on the outstanding balance; (b) bullet maturity - borrower pays only interest during the life of the loan and repays the full principal at maturity; (c) ballon amortization - smaller periodic payments, followed by a large lump-sum ballon payment of the remaining principal at maturity; and (d) custom payments, often called "cash sweeps", where the percentage of principal is repaid periodically, often linked to EBITDA or excess cash flow (albeit, one can get creative and come with other metrics).

Now, one might believe that there should be different models done for each type of term loan, however, at the end of the day the same template might be used for all and just adjust the amortiaztion line (or add a 2nd one supporting amortization) to reflect the type of loan. Below is a fragment showing the Term Loan. If you notice, the amortiation can be adjusted based on a percentage or a fixed amount (to either reflect the equal principal amortization or the ballon amortization) or just be left at 0 if it's a ballon amortization. In blue, I do emphasize the portion of the model that would be needed to reflect the cash sweep with a description below explaining the arrangement .

While they broadly share similar characteristics, their main differences lie in the repayment structure, which can take the form of equal installments, bullet maturity, or scheduled amortization across the year. An illustrative example of a term loan is presented below.

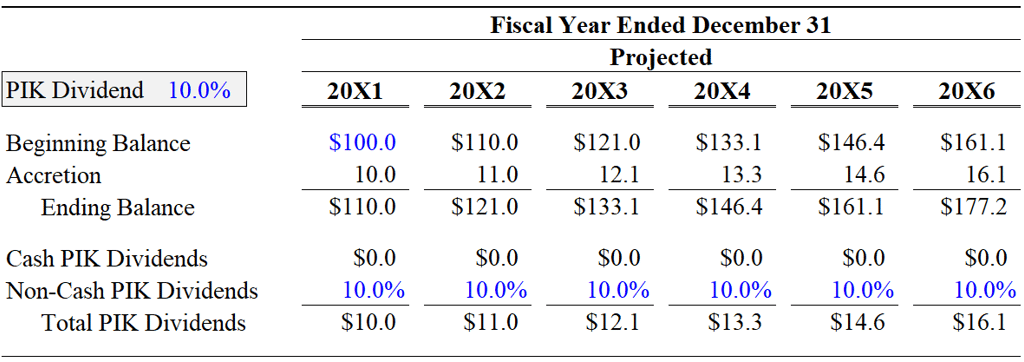

PIK Financing

PIK financing comes from the term "Pay-in-Kind" which comes the "In-Kind" trait of law which means that instead of moneis one might hand another sort of non-monetary consideration. I believe that the industry came to prefer this term instead of calling it "debt that accres the principal on top of the outstanding principal". Again, will mention that extremely long discussions could be carried about structuring PIK Financing considering they are mezzanine (for this discussion Luc Nijs, Mezzanine Financing, offers a great overview), I will simplify just to show for this article the mechanics of it.

The content on this blog, including any related materials such as newsletters, is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as financial, legal, or professional advice. Readers should consult with their own advisors before making any decisions based on this information. The author(s) disclaims all responsibility for any actions taken or decisions made based on the content of this blog. The aim is to promote general understanding and knowledge.

Contact

dealsandmandates[at]gmail.com

© 2025