NOTES ON FINANCE, MODELS, AND INVESTMENTS

Restructuring the Distressed Firm

An introductory discussion on how companies approach restructuring.

13 min read

This article is Part I of what will be a broader discussion on the main approaches a distressed firm might take when attempting to restructure itself (Part II being the "Inside Liability Management Exercises").

At first, when I set out to write this article, my plan was to begin directly with liability management exercises ("LMEs"), since they have recently attracted so much attention in the financial press. But as I worked through the topic, I realized it would be more honest - and more useful - to start with a broader perspective on how a company might end up performing LMEs in the first place. A distressed firm does not jump straight into them. Management usually explores other restructuring options first, and only by walking through those alternatives does it become clear why they might be excluded, leaving LMEs as the path forward. After all, LMEs are nothing more than restructuring tools - specific ways for a company to buy relief from creditor pressure and try to find a way out of distress. They are part of the larger restructuring toolkit, but not the whole picture.

That larger picture is what this article aims to provide.

Before diving in, the reader may find it useful to revisit our earlier pieces, A Primer on Subordination and Discussing Distressed Debt Investing, as they provide background that will make the discussion here easier to follow.

MANAGEMENT'S LENS IN RESTRUCTURING

Liability management exercises, as the name suggests, are about managing a company’s liabilities. As we have discussed in previous articles, liabilities are usually made up of obligations the company must service in cash. When a company falls into distress, it typically means that its operations are no longer generating enough liquidity to cover those obligations.

In such a situation, management has four main choices: (a) raise new equity, (b) raise new debt, (c) sell assets, or (d) renegotiate debt terms with creditors. LMEs sit inside option (d). And although they appear last on this list, they are often among the first things a company will attempt in practice. From management’s perspective, the most straightforward solution is to try to reach an agreement with creditors to reshape existing liabilities.

As such, if we rank these options broadly by complexity and challenge, from least to most, the order becomes inversed from the above: (1) renegotiate debt terms with creditors, (2) raise new debt, (3) sell assets, and (4) raise new equity. To see why LMEs can emerge as the most feasible path, it is useful to review each of the other options in turn - starting from the last one and working back to renegotiation. By process of exclusion, the role of LMEs becomes clearer.

(1) Raising New Equity

The challenge in raising new equity is that the company is distressed. Here I will come back to our analogy of the company “box,” which I have referred to often across these articles. As we discussed before, and borrowing from corporate finance theory, equityholders are last in line to be paid. They are the residual claimants, meaning they only receive payment after all creditors above them have been satisfied.

The familiar idea of “high risk, high reward” then becomes relevant here. The riskier my position becomes, meaning the lower my chances of being paid compared with creditors, the higher the return I will demand. Although this sounds theoretical, if you think about it, it's quite straightforard: If I can get a 5% return with a 15% chance of losing money, why would I accept the same 5% return if the chance of loss rises to 35%? Either I will demand a higher return or I will just position myself to the lowest risk degree to receive that 5% (this, in itself, is an interesting discussion on how much risk different layers of the capital structure are really pricing in, but that is for another time).

Now, when the company is distressed, and connecting back to this idea, if I want to bring in new investors I would need to give away pieces of my company. That would cost me much more than, for example, raising new debt at a cheaper cost. Debt has a capped cost, the interest paid to the lender, while equity takes a share of future returns, which could end up being far greater than any interest expense. This connects back to the point that payments to creditors are fixed, but payments to equityholders are only fixed in percentage terms, and are theoretically infinite in nominal terms.

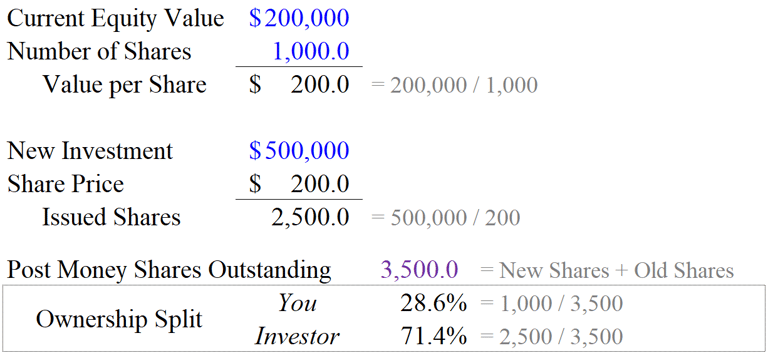

Because of this, I would hesitate to give away equity. A potential equity injection means handing over shares, which dilutes my own position, shrinking the size of my ownership. Dilution works through a simple calculation. The new investor’s share is determined by the cash he injects relative to the total post-money equity value. For instance, if my equity is $200,000 and I own 100% of the shares, and I need $500,000 to get through the distressed period, the new investor providing that $500,000 would demand 71.4% of the company. In that case, my stake falls to 28.6%. Faced with that outcome, I would disregard this option for the moment. The arithmetic of this is shown below.

Also, as a matter of fact, another challenge in raising equity is that there may be no investors willing to step in. If someone believes the distress is temporary, he might seize the opportunity—as Warren Buffett did in 2008 with Goldman Sachs when the firm was under market pressure—but if the company’s operations are fundamentally weak, investors will hesitate. In that case, even if the injection pays down debt and lightens the capital structure, the new equityholder risks being trapped in a business that keeps declining, losing value over time and struggling to exit at an attractive price.

The deeper issue, and to close this point, is that management and potential equity investors are rarely aligned. The investor, seeing management under pressure, can behave opportunistically and demand far more ownership than he would otherwise be entitled to. After all, an equity investor does not invest based on book value. He will run his own valuation, factor in uncertainty, and price future risk, which will be used to bargain with management. This turns the process into a long negotiation, where management must disclose extensive information about the company and divert focus away from day-to-day business, exactly when attention is most critical (while also risking that sensitive details leak to outsiders - even under an NDA - about how severe the situation is or other internal matters that could undermine the firm’s competitiveness). And even then, there is no guarantee of closing. At best, management might secure a break fee, a penalty paid if the investor walks away without material cause. As such, an equity injection, would be prima facie disregarded. So let's see the next option.

(2) Sale of Assets

After setting aside the equity option, management might move to the possibility of selling assets. This path is always sensitive. Whether it makes sense depends on two things: how important the asset is to the company, and how much the market is willing to pay for it. In other words, management needs to look at the sale through two lenses: (a) the potential sale price, and (b) the asset’s contribution to profitability.

Potential Sale Price. The price will be determined by the market. Selling assets under distress follows the same supply-and-demand mechanics as anything else. Highly demanded assets can fetch something close to fair value. But more niche or unique assets may sell at a discount, because only a few buyers exist, and those buyers know the company is desperate for cash. They exploit this “neediness,” bidding below intrinsic value. Management therefore needs to weigh carefully whether the proceeds will truly improve the company’s position.

Asset Contribution. The second lens is how much the asset contributes to profitability. To keep things simple, imagine we assess contribution through EBITDA. If I have a “crown asset” that carries most of the company’s profit, I would hesitate to sell it. Instead, I would focus on secondary or peripheral operations. To exaggerate, imagine Apple in distress: rather than carving out a small regional subsidiary with high costs, it sells its Apple brand but keeps operations. Clearly absurd, but it illustrates why contribution matters.

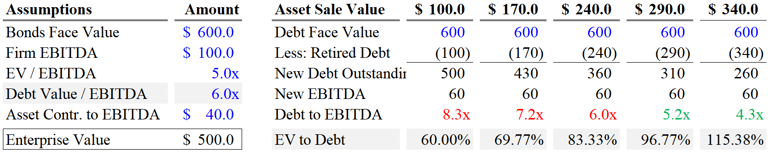

Now, let's bring those 2 together and let's see an example. Suppose the firm has $600 in total debt face value, EBITDA of $100, and at a 5x EV/EBITDA multiple, an enterprise value of $500. That means current recoveries for creditors are around 83.3% ($500 EV / $600 debt). Now, management considers selling an asset contributing $40 of EBITDA. If sold, EBITDA drops to $60, which at the same 5x multiple means EV falls to $300. On the other side of the equation, assume the asset can be sold at different prices, from $100 to $340 which would be our scenarios - 5 to be exact. Those proceeds are used to retire part of the debt. Let's see the outcomes.

What we did here was look at how, under five different scenarios, the sale of the asset—at different prices—would affect creditors. The proceeds from the sale are used to retire debt on the balance sheet (“New Debt Outstanding”). One could argue that if the bonds are actually trading at 75 in the market, the effective debt value is closer to $450, meaning the company could retire an even larger portion of its obligations. But for simplicity, I keep the numbers at face value.

From there, we run the calculations to see whether the sale leaves creditors in a stronger position or not—or, put differently, whether management has eased its pressure from creditors or only made matters worse. The way to measure this is by comparing debt multiples against EBITDA. In the scenarios shown in red, leverage worsens, meaning the debt multiple is higher than before. In the scenarios shown in green, leverage improves, showing creditors are in a relatively safer position.

This can also be expressed through the ratio of Enterprise Value to Face Value of Debt (shown in the grey boxes on the right). In the green scenarios, this ratio improves, suggesting that if the company were liquidated at that moment, creditors would actually recover more than under the no-sale baseline. For context, the current recovery without any asset sale is 83.3%. So even though, after the sale, EV falls to $300 (that is, $60 EBITDA * 5x EV/EBITDA), recoveries for creditors are nevertheless higher in higer sale price cases. In that sense, creditors get some comfort, and the company wins a bit of “goodwill” from creditors.

However, so far we have looked at this through what would make creditors happy. But putting ourselves back into management's position, we're left with a weaker operating base. EBITDA has fallen from $100 to $60, and EV has fallen as well. That hurts long-term competitiveness. The company may later need to repurchase similar assets or reinvest heavily to rebuild profitability. And selling assets is not costless as it requires negotiations, increased capital expenditure, and administrative & personnel efforts, all while management’s time and focus would be better allocate for other strategic endeavors. Let’s now see if there is another option that might (i) avoid giving away “costly” pieces of the business to outsiders, and (ii) leave the operating base intact.

(3) Raising New Debt

Now, management has disregarded the previous two options and is looking for a cheaper and less complex way to solve the distress of the firm. The next option on the table: raising new debt. Raising new debt, as the name suggests, means finding someone willing to lend money to the company. As we briefly noted earlier, equity is always more expensive than debt, so by contrast debt is cheaper.

But raising new debt carries its own complications. Put yourself in the shoes of the existing creditor. On paper, his loan already looks impaired. He is afraid of losing more money, so at the very least, he wants to make sure he does not lose any further value. Now, shift back to management. They find a potential new creditor and explain the challenges the firm is facing. The new creditor shows interest, but immediately adds a condition: he will only lend if he is given priority in repayment above the existing creditor, meaning that in an eventual bankruptcy he gets paid first, and the old creditor gets what is left. Back to the old creditor. He picks up the phone. Management says, “Hey Creditor, we found new money, but to bring them in we’d need to subordinate you and give them priority. Can we?”. If the creditor is polite, he simply refuses and explains that such a move would push him further down the capital structure, increasing his risk, or, if not so polite, he'll just lose his shit and scream "FFFUCK NO YOU FUCKING PIECE OF SHIT YOU OWED US THIS MONEY 2 MONTHS AGO. YOU'RE STILL LATE YOU FUCKING MORON (slaps the phone)". Now, management goes back to the interested creditor and says: “Hey Sir Interested Creditor, unfortunately our current creditors politely refused our proposal. Would you be willing to sit below them in the capital structure, that is, below their claims?”. The new creditor might respond that this is an extremely risky position. He could pass altogether, or he might agree but only in exchange for a much higher price on the debt, since he is taking on added risk. His decision ultimately depends on how he views the business and its worst-case scenario. If he believes the firm has a real turnaround plan that can avoid default and bring it back to profitability, he may take the risk, locking in a return that the company—because of its neediness—is forced to offer, and which he could not easily replicate with a healthy company.

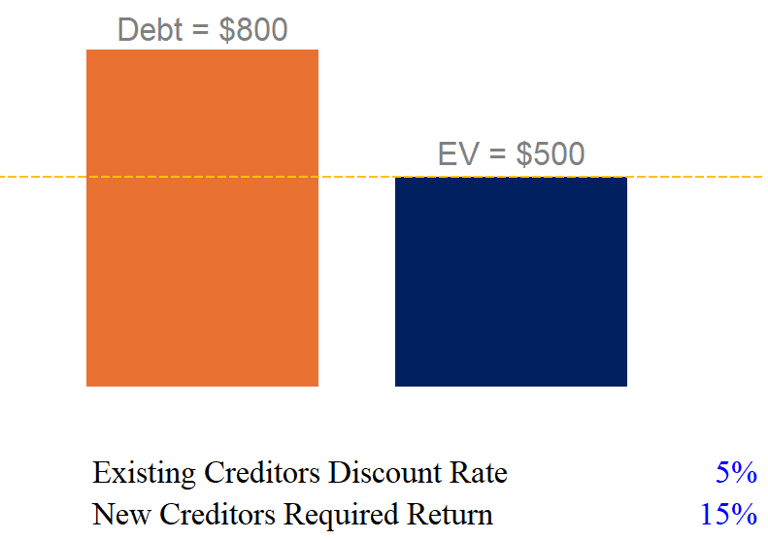

The decision to invest here is heavier than in the previous examples. To make it clearer, let’s ground it in numbers. First, we look at the current enterprise value relative to the debt size, and then we explore the different options. For our example, assume enterprise value (EV) is $500 and total debt is $800. The existing creditors discount their position at 5%, while the new creditors demand 15% to lend for one year until the company normalizes. Management estimates the company needs $300 to stabilize operations (the $300 is chosen arbitrarily here, it is not tied to the gap between EV and debt, just in case, in practice, this $300 would come from management’s forecasts of what expenses or investments are critical to keep the firm alive and put it back on track). This is the structure of the firm's "box" as of now:

As seen, the current firm value is $500 and creditors have a claim of $800. If creditors chose not to wait, they could force the company into liquidation today and realize approximately $500, assuming no major market frictions (for example, distressed buyers pushing for deep discounts or other externalities). I do also mention below the existing creditors' discount rate and the new creditors' required return, which we'll use for the examples below.

Now, let’s assume the company needs $300 to stabilize its operations. We can explore four possible scenarios one year from now, using the same numbers and assumptions:

Scenario 1: Nothing is done, everyone sits and waits.

Scenario 2: The existing creditor provides the $300 loan.

Scenario 3: A new creditor lends $300 and sits junior to the existing creditors.

Scenario 4: A new creditor lends $300 but is granted seniority over the existing creditor.

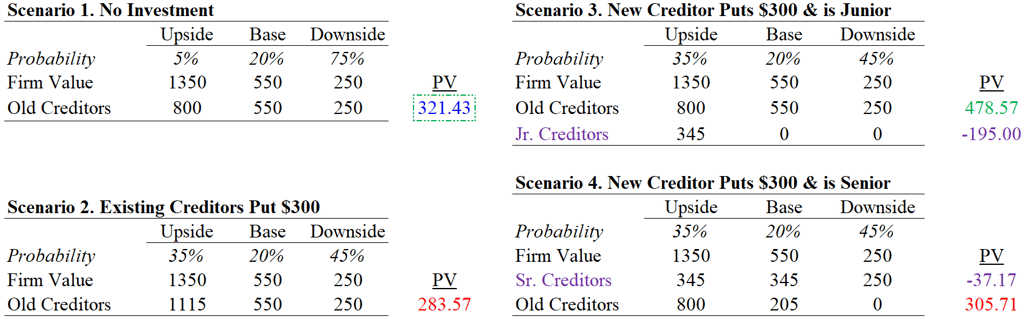

The numbers can be seen below:

Those are a lot of numbers, so let’s pause and see what we are actually doing here. We are assuming that the company faces three possible future states one year from now: an upside case, a base case, and a downside case. Each outcome carries a probability, which in practice is more of a qualitative judgment than a precise mathematical figure. In each case, stakeholders expect the firm to be worth more, remain roughly unchanged, or deteriorate further. This variation is reflected in the projected firm value.

The old creditors, holding $800 of claims, are the existing lenders in this structure. All of our analysis is forward-looking, so we need to bring those future values back to today. One year from now, as such, we discount each recovery to its present value (PV). For existing creditors, we use a 5% discount rate, assuming they resemble a standard bank lender charging relatively low interest. For new creditors, we assume they would demand around 15% on their loan, and we use the same rate to discount their potential recoveries in Scenarios 3 and 4.

This setup also resembles the “expected value” approach—multiplying the outcome in each scenario by its probability and summing across them. It looks mathematically elegant on paper, but in reality, lenders do not make decisions on a single formula. Similar three-scenario analyses are used in practice, but the decision is ultimately qualitative: how realistic the downside feels, how much confidence exists in the turnaround plan, and whether the business has a viable path to survival.

With that in mind, let’s now look at the firm under each scenario in detail (remember, that at the current value, without waiting 1 year, creditors could realize $500 PV).

Scenario 1: In this first case nothing happens. The firm is left as it is, simply hoping to recover on its own. If creditors forced liquidation today, they could recover about $500—the asset value. But if they wait one year, the present value of their recovery falls to 321. This number comes from taking the weighted probabilities of the future firm value and discounting them back at 5%. Doing nothing, as such, is hardly an option. Creditors would grow impatient.

Scenario 2: Now, suppose the existing creditors decide to lend the $300 management is asking for, in hopes of stabilizing the firm and pushing it back to profitability. Compared with Scenario 1, the chance of upside rises from 5% to 35%. The new facility comes at 5% interest, so $300 becomes $315, which, added to the $800 already outstanding, raises total claims to $1,115. The expected value is calculated in the same way as Scenario 1 - probability-weighted outcomes discounted to present value - but here we also subtract the $300 advanced. The result is a PV of 283, worse than before. The intuition is simple: if the firm has a high chance of staying impaired, or even deteriorating further, creditors would just be throwing good money after bad. For them, this option is a strong pass. Let's see scenario 3.

Scenario 3: In this case a new creditor advances the $300, sitting junior to existing creditors. He demands 15% for the risk. Running the same exercise, the existing creditors now find themselves in a better place, with their PV improving to 478. The improvement comes from the increased chance of upside, while they themselves do not risk more capital. For the new creditor, however, the picture is bleak. His NPV is negative. To break even, a $300 loan at 15% should generate about $45 in expected present value. Here it does not. In practice, as we noted earlier in Part I on LBOs, lenders often price default risk directly. This means a distressed creditor might ask for 17.5% or more to secure that $45 NPV across the weighted scenarios. But at 15%, it simply does not work. Let’s see if seniority improves things.

Scenario 4: Finally, the new creditor provides $300 but sits senior to the old creditors. The analysis shows his present value improves somewhat, but still not enough to break even. Meanwhile, the old creditors are subordinated. Their recovery in the base case falls, and their PV even dips below Scenario 1. From their point of view, sitting and waiting is preferable. And for the new creditor, Scenario 3 was already unattractive, so this structure hardly rescues it.

As such, the existing creditors feel the pressure mounting, and they are strongly tempted to push the company into bankruptcy and take their chances in liquidation. At that moment, management steps in: “No, wait, let’s discuss.” And this, naturally, leads us into debt renegotiations, which we discuss in the Part II ("Inside the Liability Management Exercises").

The content on this blog, including any related materials such as newsletters, is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as financial, legal, or professional advice. Readers should consult with their own advisors before making any decisions based on this information. The author(s) disclaims all responsibility for any actions taken or decisions made based on the content of this blog. The aim is to promote general understanding and knowledge.

Contact

dealsandmandates[at]gmail.com

© 2025